In

[1] Gillis, Verna. From liner notes of Rara in

An Outsider's Personal Journey: An audio-visual project

In

[1] Gillis, Verna. From liner notes of Rara in

Much could be said about the globalization of religious traditions, especially in the context of colonialism and imperialism that produced subsidiary institutions like slavery and caste systems. Many times religious conversion was used as a tool to aide these processes. If so afforded, these diverse forms of divine adoration take on distinct variations across the globe.

So is true of Gaga, a variation of Haitian Rara yet practiced in the

Using the sounds of Gaga as a basis for comparison, I plan to juxtapose Catholicism with them in order to substantiate the claim Aidan Kavanagh makes on theologia prima, or primary theology versus theologia secunda, or secondary theology.[1] According to Kavanagh, primary theology is the dynamic response “suffered” in liturgical events while secondary theology is the didactic, systematic approach to thinking about liturgical events. I contend that Gaga could be considered a “dynamic response” to the umbrella catechism proliferated throughout the

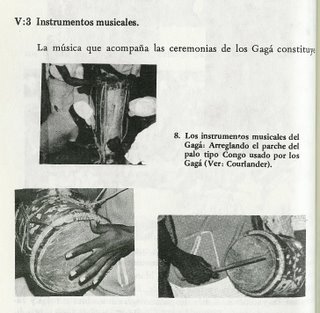

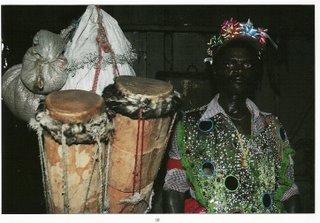

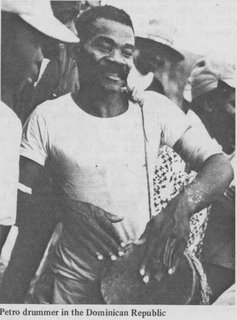

a gag'g drummer with two congó drums.

a gag'g drummer with two congó drums. a gagá drummer shown with metal guiro. Native to the Dominican Republic, the guiro is the fundamental scraper found in other genres such as bachata and merengue. Scrapers and other like metallophones are also characteristic of rará ceremonies, however only in the Dominican Republic do we find such usage of the guiro.

a gagá drummer shown with metal guiro. Native to the Dominican Republic, the guiro is the fundamental scraper found in other genres such as bachata and merengue. Scrapers and other like metallophones are also characteristic of rará ceremonies, however only in the Dominican Republic do we find such usage of the guiro. a gagá drummer marching.

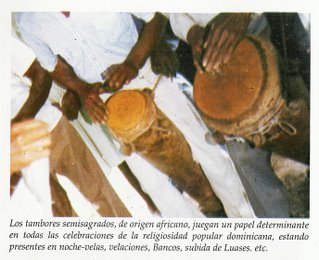

a gagá drummer marching. Congó drums shown with pegs.

Congó drums shown with pegs.

Becker, Judith. Deep Listeners: Music, Emotion and Trancing.

McAllister, Elizabeth. Rara! Vodou, Power, and Performance in

Alegría-Pons, José Fransisco. Gagá y Vudú en la República Dominicana. Santo Domingo: Ediciones El Chango Prieto, 1993.

Rosenberg, June. El Gaga. Santo Domingo: Editora de la Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, 1979.

Tejada Ortiz, Dagoberto. Cultura Popular e Identidad Nacional (Tomo II). Santo Domingo: Consejo Presidencial de Cultura Instituto Dominicano de Folklore, 1998.

Tejada Ortiz, Dagoberto, et al. Religiosidad Popular y Psiquiatría. Santo Domingo: Editora Corripio C. por A., 1995.

My group now seated, several members of the community (who I had seen periodically earlier in the day) arranged themselves in a row on the far end of the building. They were dressed in the same clothing they had on earlier in the day, only this time they all had bandannas or scarves of various colors. We were told that presiding over today's ceremony was a priest who had recently arrived from Haiti. But before he could enter the room and begin the ceremony, the woman who seemed to be leading the procession of individuals claimed that the drums (located in the far corner) had to be "blessed first."

My group now seated, several members of the community (who I had seen periodically earlier in the day) arranged themselves in a row on the far end of the building. They were dressed in the same clothing they had on earlier in the day, only this time they all had bandannas or scarves of various colors. We were told that presiding over today's ceremony was a priest who had recently arrived from Haiti. But before he could enter the room and begin the ceremony, the woman who seemed to be leading the procession of individuals claimed that the drums (located in the far corner) had to be "blessed first."

Dressed in a blue shirt, blue shorts and a blue bandanna, he recited lines in Creole accompanied by the drummers playing at moderate tempo and mid volume. In a somewhat rehearsed fashion, the drummers seemed to play more intricate patterns according the the force and ferocity of the priest's voice. At one point in the ceremony, the priest stopped and exited. The group behind him started to dance as if they were battling peaceably. As the rest of the group sang a song, The dancers remained in tempo and in stride as they

Dressed in a blue shirt, blue shorts and a blue bandanna, he recited lines in Creole accompanied by the drummers playing at moderate tempo and mid volume. In a somewhat rehearsed fashion, the drummers seemed to play more intricate patterns according the the force and ferocity of the priest's voice. At one point in the ceremony, the priest stopped and exited. The group behind him started to dance as if they were battling peaceably. As the rest of the group sang a song, The dancers remained in tempo and in stride as they  jumped and lunged towards each other. The drummers mimicked each thrust with an emphatic pattern on the drum. After the "battle" was over, the priest re-entered, this time dressed in a red shirt with matching red shorts. He began to mumble words under his breath while assistant prepared a tray that included several razorblades, matches, a bottle of rum and a bundle of short sticks. Though I predicted what he was going to do next, I still was not prepared for what I witnessed. As the drummers played faster and faster, the priest drank from the bottle of rum and lit the sticks. With a bundle in each hand, he proceeded to dance around holding the sticks to his feet for several

jumped and lunged towards each other. The drummers mimicked each thrust with an emphatic pattern on the drum. After the "battle" was over, the priest re-entered, this time dressed in a red shirt with matching red shorts. He began to mumble words under his breath while assistant prepared a tray that included several razorblades, matches, a bottle of rum and a bundle of short sticks. Though I predicted what he was going to do next, I still was not prepared for what I witnessed. As the drummers played faster and faster, the priest drank from the bottle of rum and lit the sticks. With a bundle in each hand, he proceeded to dance around holding the sticks to his feet for several seconds. Unlike, stereotypical magic shows where the crowd goes silent before the magician performs his feat, the priest's acts were accompanied by an ever-growing, powerful drum beat. He seemed to be aided by the drums. While it must have took an insane amount of mind and body control to perform such feats, each jump and twist he did around the flames seemed to be matched by an equal hit or slam on the drums. As the priest continue to express his control over the

seconds. Unlike, stereotypical magic shows where the crowd goes silent before the magician performs his feat, the priest's acts were accompanied by an ever-growing, powerful drum beat. He seemed to be aided by the drums. While it must have took an insane amount of mind and body control to perform such feats, each jump and twist he did around the flames seemed to be matched by an equal hit or slam on the drums. As the priest continue to express his control over the  fire, I became more and more interested in the drummers and drums in the background. The incessant beat was mesmerizing and entrancing. A percussionist myself, I was fascinated by the polyrhythmic patterns the lead drummer appeared to play with ease. Requiring great amounts of stamina, they played during the entire ceremony. Everything in the ceremony seemed to be guided by or at least accompanied with drums. To me, the sound of the drums was the center of attention. While I can't recall much of anything that was said in the ceremony (it was all in Haitian Creole anyway), I do remember the complexity of the drum rhythms. As an outsider, I was "moved" by the drum patterns. They were reminiscent of African rhythms I had heard before (which I'm almost positive that is where they were derived), yet had their own interesting spin. They sound is difficult to express in words, but what dominated my thoughts as soon as the ceremony was over was that very idea: despite the drama related to race, racial politics and cultural backlash towards anything African, I was in DR and this was undoubtedly Dominican. At Batey Libertad, the majority of its inhabitants were born there or in the Dominican Republic. Most spoke Spanish, Haitian Creole, French and some English. My first experience at a Vodou ceremony seemed far less "Haitian" than I expected, and as I found out later, was much more related to the Dominican experience than I had first believed. That experience at the ceremony reaffirmed my belief in the prevalence of African roots in the Dominican Republic.

fire, I became more and more interested in the drummers and drums in the background. The incessant beat was mesmerizing and entrancing. A percussionist myself, I was fascinated by the polyrhythmic patterns the lead drummer appeared to play with ease. Requiring great amounts of stamina, they played during the entire ceremony. Everything in the ceremony seemed to be guided by or at least accompanied with drums. To me, the sound of the drums was the center of attention. While I can't recall much of anything that was said in the ceremony (it was all in Haitian Creole anyway), I do remember the complexity of the drum rhythms. As an outsider, I was "moved" by the drum patterns. They were reminiscent of African rhythms I had heard before (which I'm almost positive that is where they were derived), yet had their own interesting spin. They sound is difficult to express in words, but what dominated my thoughts as soon as the ceremony was over was that very idea: despite the drama related to race, racial politics and cultural backlash towards anything African, I was in DR and this was undoubtedly Dominican. At Batey Libertad, the majority of its inhabitants were born there or in the Dominican Republic. Most spoke Spanish, Haitian Creole, French and some English. My first experience at a Vodou ceremony seemed far less "Haitian" than I expected, and as I found out later, was much more related to the Dominican experience than I had first believed. That experience at the ceremony reaffirmed my belief in the prevalence of African roots in the Dominican Republic.